And I might have invited Jack over for dinner had my house been more of what it once was and less of what it was now, which was — as I glanced perplexedly around — apparently inhabited by psychotic people.

And because I felt I needed to demonstrate to my friend Ross what a house such as this might look like and though this was far in advance of when you could make an actual video with your device, I held up the phone’s receiver and slowly moved it along taking in the hypothetical panoramic so Ross could at least be listening with me to the invisible space-staticky hiss of a household being buried under an avalanche of random, everyday chaos.

What had happened was evidently that The Householder — that would be me — was frankly no longer coping. No longer coping sounded like an okay diagnosis, but how had this come to be?

Said Householder couldn’t tell you, as Said Householder had gone numb and had been watching out the window impassively, without identifiable reaction, on the morning the Mayflower moving truck pulled up and began offloading 2073 pounds of household furnishings into her already furnished house.

My mother-in-law had been with us awhile by then, can’t pinpoint the time, as my usual more-than-adequate narrative memory was developing some startling gaps. This was simply unlike me, in that I’ll more usually have the even more than adequate explanation for everything.

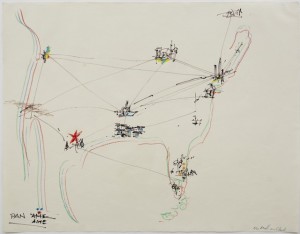

“Maps of the U.S. from Memory” by Gordon Matta-Clark, via @hyperalergic

I’d been sitting on the gray velvet loveseat drinking tea when the furniture arrived, struggling to figure all this out. I’d entered into a fugue state, I understood, and was now suffering cognitive losses that paralleled my mother-in-law’s: <em>Erosion of reasoning capability? Check. Diminishment of verbal skills? Check — me thinking all the while: What a terrible plight for a writer!

Which I’d talk about at length and gymnastically to anyone who’d listen, telling you all about how being around someone with dementia for extended periods very literally causes cognitive dysfunction. It was one of Min’s caretakers at her daycare facility who’d explained this to me, its coming up when I asked him their address on the phone and he’d answered:

I honestly have no idea.

Or to put it in literary terms: We all now existed in what James Joyce called the General Paralysis of the Insane, GPI being your bewilderingly awakening to such a catatonic morass that you’re left to be dumbfoundedly asking: Wait a minute…what’s just happened to my life?

Joyce claimed GPI afflicted the entire nation of Ireland.

And there now seemed to exist in the rooms around me doubles of many household objects, both necessary and ornamental, the duplicated items grouped together as if they might be going on sale. Now fine old rugs lay atop fine old rugs and convocations of chairs huddled here and there awaiting gossips who cluster in corners to whisper behind their hands how in Jane’s House — once so neat and orderly-there were now all these occasional tables for which there were no occasions.

But more distressing than the crowding oppression of all these unmanageable objects were the widening gaps in narrative memory, anything that might explain all this to me as I sat on the couch or countertop, locked in the bathroom, drinking. Now the plot part of my brain had seemingly switched off, now I was failing at the job of Sequencing and so no longer reliably knew myself in the mirror.

Now, in addition to the twice-too-much furniture, there were five of us to worry about: two children, one mid-range used-to-be-grownup, the two full-sized adults, also a miniature dog of the yappy variety, one with a high, piercing bark. We got this dog during That Vague Time where motives were lost, found him, kept him out of confusion over what else to do with him.

But you were a foundling too, I’d say to myself, wine blind and addressing the image in the mirror. You were orphaned, your aunt took you in. You don’t let go of lost dogs or inconvenient people. Instead, you take especially good care of them.

So here was the pup my kids and I’d picked up at the University Art Museum hiding beneath one of the earthquake struts, drenched from the rain. We’d lured him to us with vegetarian soup, brought him home wrapped in our chlorine-reeking towels.

My children and I’d been swimming at the Berkeley City Club right down the street on Durant. It was designed by Julia Morgan, opened in 1930 as a women’s club and residency — my rich grandmother stayed there while up from LA to visit my father at Cal because rooms cost $3 a night and my rich grandmother was cheap.

There were no words for the lure of that club for me, how much I now wanted to simply pack up one small suitcase, my typewriter and current manuscript, leave home and go live there, except I couldn’t because I was responsible for not only my two small children but also this foundling dog, also my mother-in-law, who’d come to us for a visit, been diagnosed with mid-stage Alzheimer’s disease and so turned into the house guest who’d never leave, becoming my immediate family!

The accidental way we’d got this dog was indicative of how most things occurred during that Time Period, when all decisions made are now cloaked in an even fundamental mystery.

The kids and I first thought he was young, maybe a half-grown cocker, but the dog turned out to be old and mean, a purebred Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, Ruby Variety, of surly disposition. That first day we had him he leaped up, as my kids’ dad bent over to pet him, and bit the man on the nose.

The dog had bulging eyes that wept watery pinkish tears, also, according to our vet, undescended testicles. Maybe an old person’s pet and not well cared for, maybe the miscreant product of some puppy mill.

My daughter and son were two or three and five or six when their grandmother arrived, again precise details now lost. My diminutive mother-in-law flew from the East for a visit. She never went back home. It was her furniture being offloaded from the Mayflower truck as I watched.

The furniture’s arriving cinched it. She was ours now, as her furniture said: Yours, irrevocably.